This article was first published on The Conversation

This week we’re exploring the state of nine different policy areas across Australia’s states, as detailed in Grattan Institute’s State Orange Book 2018. Read the other articles in the series here.

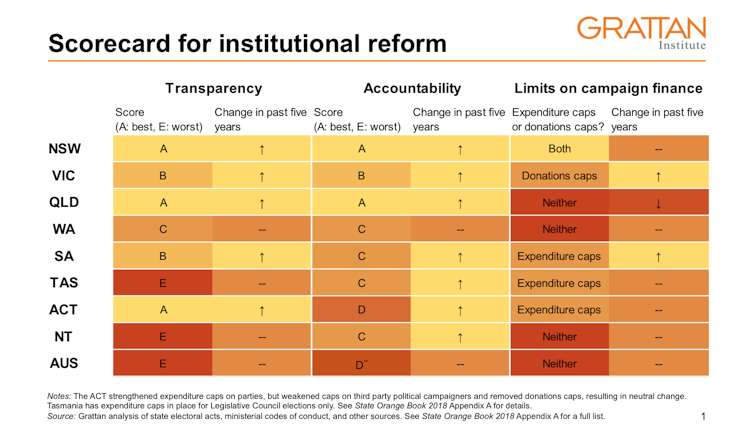

When it comes to cleaning up Australian politics, some states are doing much better than others – and almost all are showing up the Commonwealth government.

Grattan Institute’s State Orange Book 2018, released this week, compares the states and territories on the strength of their political institutions and checks and balances (among other things). Queensland and NSW received an A grade from Grattan for political transparency and accountability. Both have stronger rules than other states on lobbying and political donations.

Western Australia, once a leader after introducing lobbying reforms in the mid-2000s, is now only middle of the pack. Tasmania and the Northern Territory are the poorest performers – both get an E for transparency of their political dealings. The Commonwealth government sits with them at the back of the pack.

Some states are highly transparent

Some states and territories have made political lobbying much more open to the public gaze. NSW, Queensland and the ACT now publish ministerial diaries, so voters can see who is trying to influence whom, and when. All jurisdictions except the Northern Territory have a lobbyists’ register, and Queensland and South Australia require lobbyists to publish details on which ministers and shadow ministers they meet with.Most states have also introduced reforms to help voters “follow the money” in politics. NSW, Victoria, Queensland and the ACT require donations of $1,000 or more to be publicly declared. Only Tasmania has the same high threshold as the Commonwealth government ($13,800). Most states and territories require political parties to aggregate small donations from the same donor and declare them once the sum is more than the disclosure threshold. But Tasmania, the Northern Territory and the Commonwealth have left this loophole gaping.

Read more: Influence in Australian politics needs an urgent overhaul – here's how to do it

The disclosure threshold for donations should be no higher than $5,000 in all states and territories, and at the federal level. And donations should be disclosed quickly – preferably within seven days during election campaigns, as now happens in Queensland, South Australia and the ACT, or at least within 21 days, as in NSW and Victoria. Tasmania, and the Commonwealth, still leave us waiting up to 19 months to find out who donated to political parties during elections.

State governments are becoming more accountable

Almost all states have improved their level of accountability to voters in recent years. All states and territories now have a ministerial code of conduct, setting out standards of ethical behaviour, including rules on accepting gifts and hospitality. And all have introduced a similar code for other parliamentarians, or are close to adopting one. The Commonwealth has a code only for ministers.But enforcement of the codes is typically weak, meaning the codes are more like guidelines than rules. In most states, the premier or the parliament ultimately determine sanctions for misconduct. Enforcement can easily become political.

NSW and Queensland have independent oversight of their codes of conduct. The other states and territories should follow. And there should be meaningful sanctions for misconduct and for breaching disclosure rules – such as large fines or jail time, as applies in NSW.

Read more: Australians think our politicians are corrupt, but where is the evidence?

The states have also made progress in exposing and tackling corruption. All states and the NT now have dedicated anti-corruption or integrity agencies that provide some reassurance to the public that serious issues will be confronted. There is one on the way in the ACT.

Only the Commonwealth lags in this area. It would be naïve to assume that corruption at the federal level is less prevalent or serious than at state level. Establishing an equivalent agency at the federal level should be a priority for the Commonwealth.

All states and the Commonwealth can do better

The appearance, and sometimes reality, of political decisions favouring special interests or politicians’ self-interest has contributed to voter disillusionment and falling trust in government. Voters want their governments – local, state, and federal – to clean up their act and put integrity reforms high on the agenda. Reforming political institutions is both good politics and good policy.Every state and territory could do better by looking at best practice around the country. States and territories should fill the gaps we have identified in their transparency and accountability frameworks. They should also introduce a cap on political advertising expenditure during election campaigns, to help reduce the power of individual donors and free-up parliamentarians to do their jobs instead of chasing dollars.

Most of all, our laggard Commonwealth government needs to lift its game. Federal ministers should be required to publish their diaries. A list of all lobbyists with security passes to federal Parliament House should be made public and kept up-to-date. Big donations to federal political parties should be disclosed in close to “real time”. And voters should have confidence that misconduct by federal MPs will be independently investigated and punished.

Otherwise, the crisis of trust in Australian politics will only grow.

Danielle Wood, Program Director, Budget Policy and Institutional Reform, Grattan Institute; Carmela Chivers, Associate, Grattan Institute, and Kate Griffiths, Senior Associate, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment